Neural Implicit Representation

Published:

Welcome to this guide on Neural Implicit Representations (NIR), an advanced approach to 3D reconstruction and graphics. Explore concepts like implicit functions, occupancy networks, volumetric rendering, and Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF), enabling high-resolution 3D modeling.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Definition

- Representations - Voxel - Point - Mesh - Occupancy Networks

- Mesh Extraction - Marching Cubes - Multiresolution Iso-Surface Extraction (MISE)

- Differentiable Volumetric Rendering

- Neural Radiance Fields

- References

Introduction

In this tutorial, we will approach the Neural Implicit Representation principals and its applications in computer vision, graphics, and robotics.

Definition

Implicit Neural Representation (INR) is a novel concept within machine learning and computer graphics that represents an object or scene as a continuous function, rather than an explicit surface or structure. Implicit Neural Representation aims to learn a mathematical function \(f(x, y) = 0\) or implicit representation that can generate the desired data points.

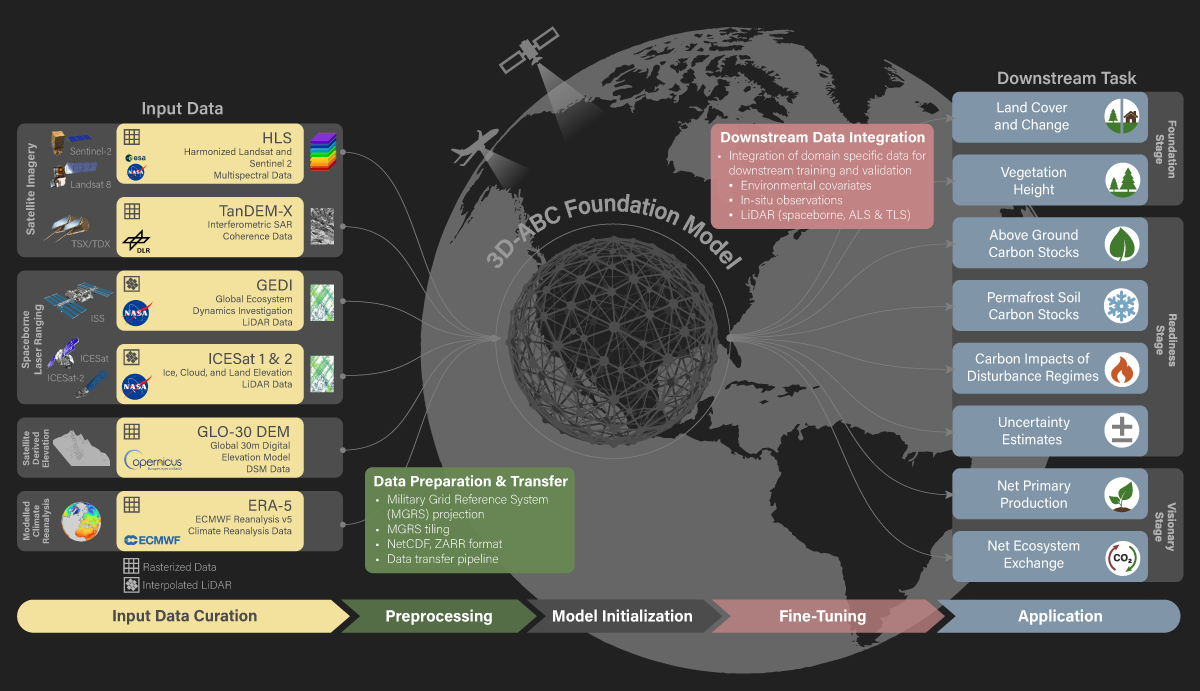

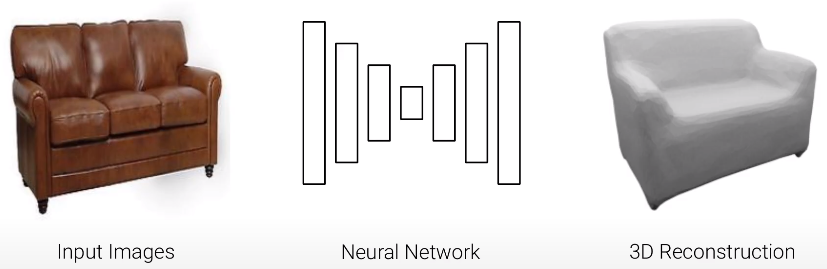

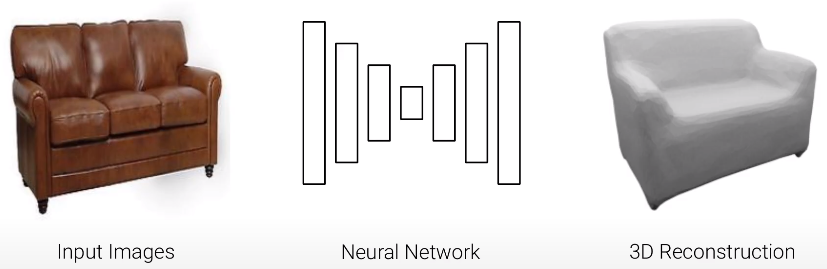

Learning-based approaches for 3D reconstruction have gained popularity for their rich representation of 3D models, compared to traditional Multi View Stereo (MVS) algorithms. Through literature, Deep Learning approaches are categorized into three representations:

Representations

What is a good representation?

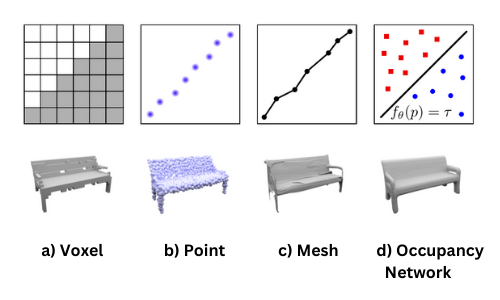

Voxel

Voxels are easy to process by neural networks and commonly used in generative 3D tasks by discretizing the space into a set of 3D voxel grids. However, due to their cubic memory \(O(n^3)\), voxel representations are limited to small resolutions of the underlying 3D grid. [2]

Point

As an alternative to the voxel representation, the output can be represented as a set of 3D point clouds. However, the point representation doesn’t preserve model connectivity and topology, hence requiring post-processing steps to extract a 3D mesh. The point representation is also limited by the number of points, which affects the resolution of the final model. [3]

Mesh

Representing the output as a set of triangles (vertices and faces) is a very complicated structure that requires a reference template from the same object class. Yet, the approach is still limited by memory requirements and the resolution of the mesh. [4]

Occupancy Networks

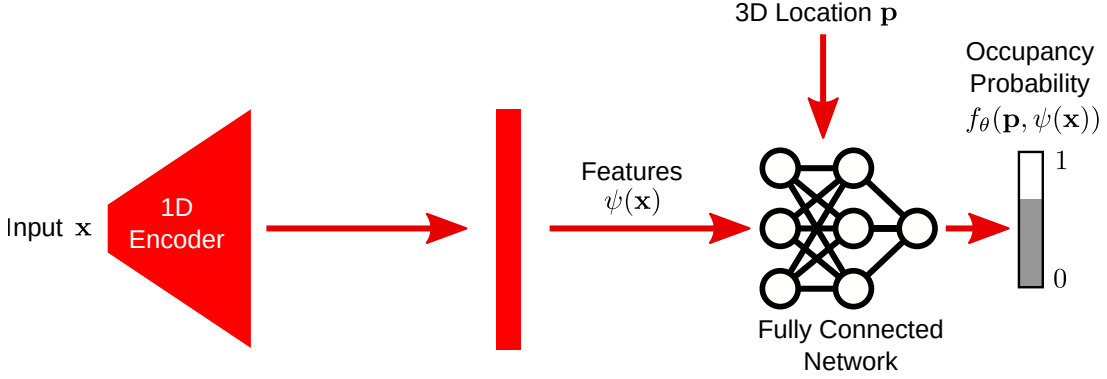

The Occupancy Network implicitly represents the 3D surface as a decision boundary of a nonlinear classifier. For every point \(\mathbf{p} \in \mathbb{R}^3\) in 3D space, the network predicts the probability of the point being inside the object. The occupancy function is defined as:

\[\mathbf{o} :\mathbb{R}^3 \rightarrow [0, 1]\]The occupancy function is approximated by a deep neural network \(f_\theta\) with parameters \(\theta\), that takes an observation \(\mathbf{x} \in X\) as input condition (e.g., image, point cloud…), and maps \(\mathbf{p} \in \mathbb{R}^3\) to a probability in \([0, 1]\).

For each input pair \((p, x)\), we can write the occupancy network function as:

\[f_\theta : \mathbb{R}^3 \times X \rightarrow [0, 1]\]

The advantage of the occupancy network is its continuous representation with infinite resolution. It is not restricted to a specific class as in mesh representations and has a low memory footprint.

To learn the parameters \(\theta\), we randomly sample 3D points (e.g., \(K = 2048\)) in the volume and minimize the binary cross-entropy (\(BCE\)) loss function:

\[L(\theta, \psi) = \sum_{j=0}^{N} BCE(f_\theta(p_{ij}, z_i), o_{ij})\]- In practice, we sample the 3D points uniformly inside the bounding box of the object.

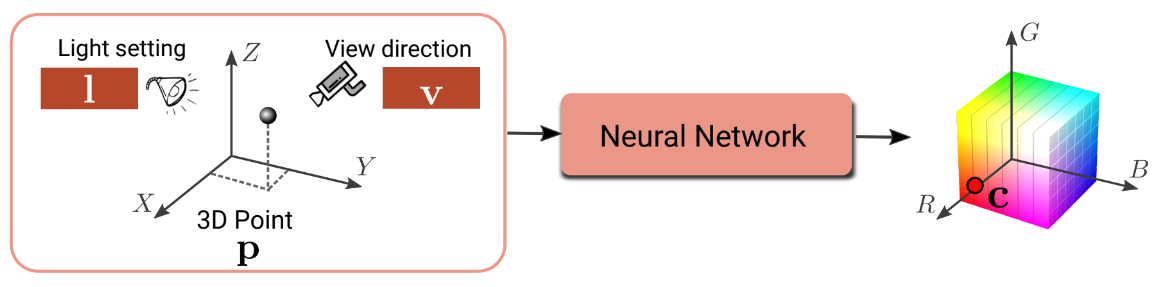

Appearance, Geometry, and Surface Properties

The implicit representation can be extended to include more object properties and reasoning, such as surface lighting and viewpoint. The occupancy network can be conditioned by the viewing direction \(v\) and light location \(l\) for any 3D point \(p\). For each input tuple \((p, v, l)\), we write the occupancy network function as:

\[f_\theta : \mathbb{R}^3 \times \mathbb{R}^3 \times \mathbb{R}^M \rightarrow [0, 1]\]

The network encodes both an input 2D image and the corresponding 3D shape into latent representations \(z\) and \(s\), as a conditioning to the occupancy network. The model predicts the occupancy probability for each 3D point \(p\) and the color \(c\), i.e., Surface Light Fields.

- The light \(l\) denotes the light source parameters, such as direction, color, and intensity.

The network is trained to minimize the photometric loss function between the predicted image \(I\) and the input image \(\hat{I}\):

\[L(I, \hat{I}) = \left\| I - \hat{I} \right\|_1\]Convolutional Occupancy Networks

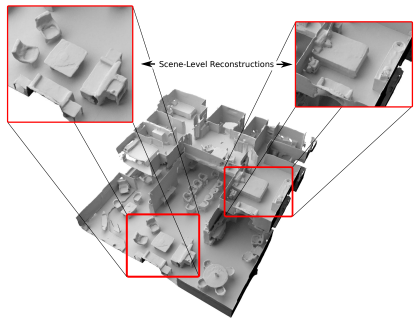

Large-scale representation learning for 3D scenes?

Implicit Neural Representations have demonstrated good results for small objects and scenes. However, most approaches fail to scale to large scenes due to:

- Previous architectures not incorporating local information in the observation.

- A lack of exploitation of translational equivariance in 3D scenes.

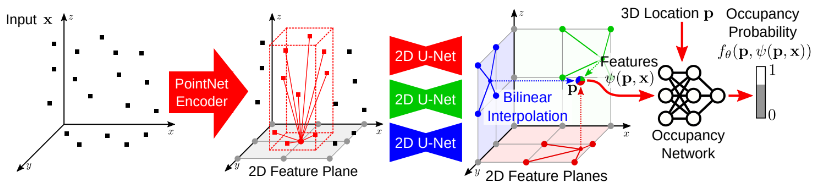

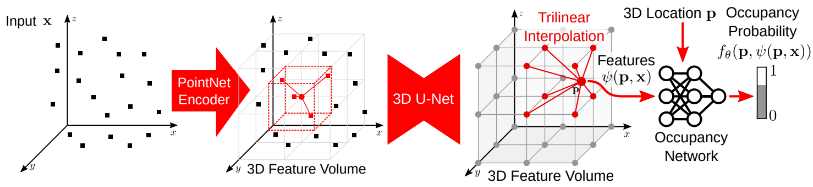

Convolutional Occupancy Networks introduce convolutional networks into implicit modeling for accurate and rich large-scale 3D scenes. The convolutional backbone incorporates both local and global information, leveraging inductive biases—specifically translational equivariance—for better generalization.

We process the inputs through an encoder to extract feature embeddings:

- PointNet for input point clouds

- 3D-CNN for input voxels

Planar Encoding

For each input point, we perform an orthographic projection onto a canonical plane aligned with the coordinate axes, discretized at resolution \(H \times W\) pixels.

We aggregate features projected onto the same pixel using average pooling, resulting in planar features of dimensionality \(H \times W \times d\).

Volume Encoding

Volumetric encodings capture 3D information better than 2D planar encodings. However, their resolution is limited by memory constraints. Average pooling is performed over the voxel cells, producing a feature volume of shape \(H \times W \times D \times d\).

Convolutional Decoder

The convolutional decoder processes the resulting feature planes and volumes using 2D and 3D U-Net architectures. These capture both local and global contexts while preserving translation equivariance in the output features, enabling structured reasoning.

Occupancy Prediction

Given the aggregated features, we predict the occupancy probability for each 3D point \(p\) by projecting it onto corresponding planes and querying feature vectors using bilinear interpolation. For multiple planes, their features are summed. For volume features, trilinear interpolation is used.

Let \(x\) be the resulting feature vector at point \(p\), and \(\psi(p, x)\) the queried feature. The occupancy probability is predicted via a fully connected occupancy network:

\[f_\theta : (p, \psi(p,x)) \rightarrow [0, 1]\]

Mesh Extraction

Mesh extraction is a post-processing step used to convert the continuous occupancy field into a 3D mesh.

Marching Cubes

The Marching Cubes algorithm extracts a polygonal mesh from a 3D scalar field. It identifies the isosurface by evaluating scalar values at cube vertices and generates triangles accordingly.

Algorithm steps:

- Divide the 3D space into a grid of cubes (each with 8 vertices).

- Evaluate each vertex and compare its value to a threshold \(\tau\).

- Determine cube configuration and triangulate the intersected edges.

- Generate polygons per cube and merge them into a full mesh.

- Optimize the mesh by removing duplicate vertices and redundant edges.

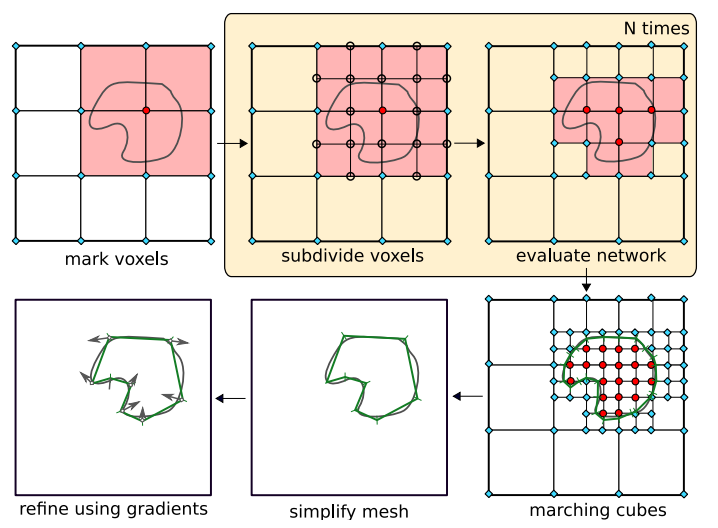

Multiresolution Iso-Surface Extraction (MISE)

MISE is a method for incrementally building an octree to extract high-resolution meshes from the occupancy function.

We divide the 3D space into an initial resolution (e.g., \(32^3\)), and compute the occupancy function \(f_\theta(p, x)\) for each cell.

We set a threshold value \(\tau\), and mark a grid point as “occupied” if \(f_\theta(p, x) > \tau\).

We subdivide each occupied cell into 8 sub-cells and re-evaluate \(f_\theta(p, x)\).

The process repeats until the desired resolution is reached.

Finally, we apply the marching cubes algorithm to extract the iso-surface defined by the threshold \(\tau\):

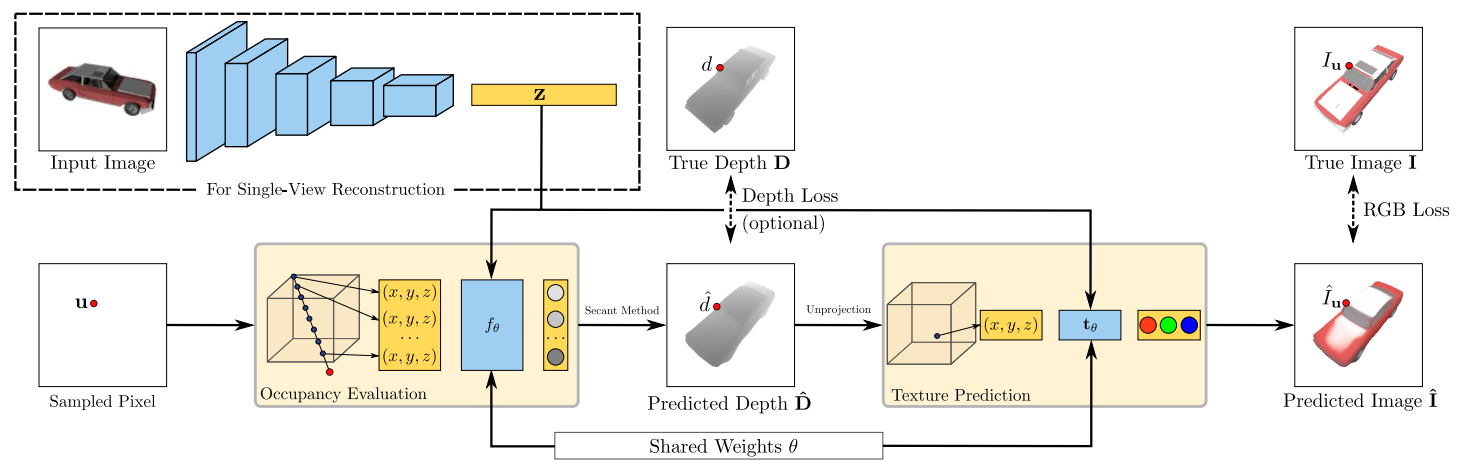

Differentiable Volumetric Rendering

Learning from images only!

Learning-based 3D reconstruction methods have shown impressive results, but typically require 3D supervision from real-world or synthetic data.

Differentiable Rendering aims to learn 3D reconstruction from RGB images only, by using implicit representations to derive depth gradients.

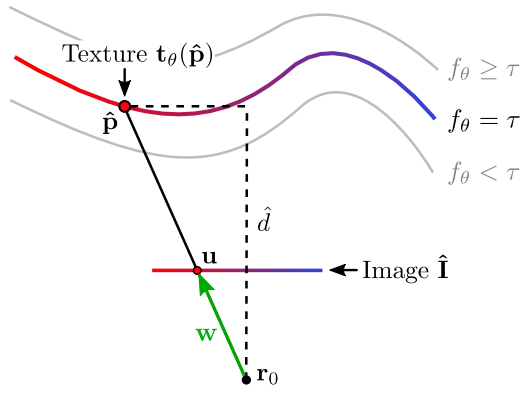

An input image is processed with an encoder to extract a latent representation \(z \in \mathbb{Z}\), which conditions the occupancy network \(f_\theta\). The 3D surface shape is defined by a threshold \(\tau\), such that \(f_\theta(p, z) = \tau\).

The texture of a 3D shape is modeled using a texture field \(t_\theta: \mathbb{R}^3 \times \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3\), which regresses the RGB color for each point \(p \in \mathbb{R}^3\), conditioned on \(z\). The texture on the surface corresponds to values of \(t_\theta\) at \(f_\theta = \tau\).

We define the photometric loss between the rendered image \(\hat{I}\) and the ground truth image \(I\) as:

\[L(\hat{I}, I) = \sum_{u} \left\| \hat{I}_u - I_u \right\|_1\]- \(u\) denotes the pixel location.

For a camera at location \(r_0\), we render \(\hat{I}\) at pixel \(u\) by casting a ray from \(r_0\) through \(u\), and compute the intersection \(\hat{p}\) with the surface \(f_\theta(p) = \tau\).

Each ray is given by \(\hat{p} = r_0 + d \cdot w\), where \(d\) is the depth. Since \(\hat{p}\) depends on \(\theta\), we compute its derivative using the chain rule:

\[\frac{\partial \hat{p}}{\partial \theta} = w \cdot \frac{\partial \hat{d}}{\partial \theta}\]Applying the chain rule to the photometric loss:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \theta} = \sum_{u} \frac{\partial L}{\partial \hat{I}_u} \cdot \frac{\partial \hat{I}_u}{\partial \theta}\] \[\frac{\partial \hat{I}_u}{\partial \theta} = \frac{\partial t_{\theta}(\hat{p})}{\partial \theta} + \frac{\partial t_{\theta}(\hat{p})}{\partial \hat{p}} \cdot \frac{\partial \hat{p}}{\partial \theta}\]To solve for \(\frac{\partial \hat{p}}{\partial \theta}\), we apply the surface constraint \(f_\theta(\hat{p}) = \tau\) and obtain:

\[\frac{\partial \hat{p}}{\partial \theta} = w \cdot \frac{\partial \hat{d}}{\partial \theta} = -w \cdot \left(\frac{\partial f_\theta(\hat{p})}{\partial \hat{p}} \cdot w \right)^{-1} \cdot \frac{\partial f_\theta(\hat{p})}{\partial \theta}\]Hence, computing the gradient of the surface depth \(\hat{d}\) with respect to \(\theta\) involves differentiating \(f_\theta\) at \(\hat{p}\) with respect to both \(\theta\) and the spatial location \(\hat{p}\).

Neural Radiance Fields

Can we render a novel photo-realistic view of the scene from an implicit representation?

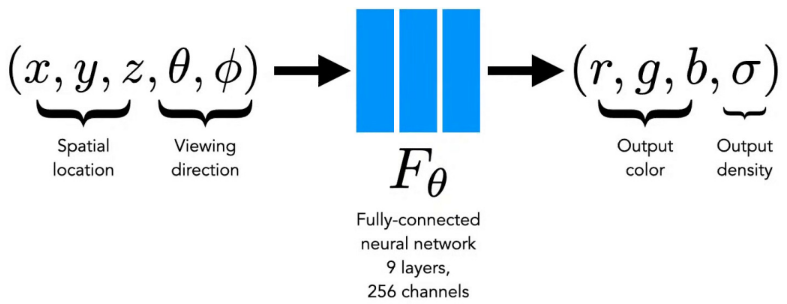

Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) is a method for synthesizing novel views of a scene from a sparse set of input views. NeRF maps a 3D spatial location \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^3\) and a 2D viewing direction \(\mathbf{d} \in \mathbb{R}^2\) to a color \(\mathbf{c} \in \mathbb{R}^3\) and a volume density \(\sigma \in \mathbb{R}\). The function is implemented as an MLP and defined as:

\[f: (\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{d}) \rightarrow (\mathbf{c}, \sigma)\]- Density \(\sigma\) describes the opacity of a 3D point and is predicted solely from \(\mathbf{x}\).

- Color \(\mathbf{c}\) is predicted based on both \(\mathbf{x}\) and the viewing direction \(\mathbf{d}\).

- \(d\) is the direction from the camera center to the 3D point.

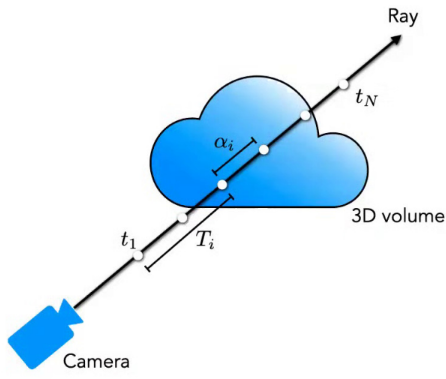

Unlike DVR, NeRF does not evaluate color only at the surface intersection. Instead, it evaluates color and density at multiple points along the ray and integrates them.

The rendering equation for a ray \(r(t) = r_0 + t \cdot d\) is:

\[C \approx \sum_{i=1}^{N} T_i \cdot \sigma_i \cdot C_i\]- \(C_i\) is the color at the \(i\)-th sample point,

- \(T_i\) is the accumulated transmittance weight.

The alpha \(\alpha_i\), or opacity at each point, is defined as:

\[\alpha_i = 1 - \exp(-\sigma_i \cdot \Delta t)\]NeRF Model

class NeRF(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_features=3, hidden_features=256, out_features=4, num_layers=8, viewdir_features=128):

super(NeRF, self).__init__()

self.density_mlp = self._make_mlp(in_features, hidden_features, out_features, num_layers)

self.viewdir_mlp = self._make_mlp(in_features + viewdir_features, hidden_features, out_features, 1)

def _make_mlp(self, in_features, hidden_features, out_features, num_layers):

layers = []

for _ in range(num_layers):

layers.append(nn.Linear(in_features, hidden_features))

layers.append(nn.ReLU())

in_features = hidden_features

layers.append(nn.Linear(hidden_features, out_features))

return nn.Sequential(*layers)

def forward(self, coords, view_dir):

density_feature = self.density_mlp(coords)

sigma = torch.sigmoid(density_feature[:, 0])

view_input = torch.cat([density_feature[:, 1:], view_dir], dim=1)

color = torch.sigmoid(self.viewdir_mlp(view_input))

return sigma, color

NeRF Training: We sample a set of rays from the input images and optimize the network parameters (\theta) to minimize the reconstruction loss function:

\[L(\theta) = \min_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left\| \hat{C}_i - C_i \right\|_2^2\]# loss

def nerf_loss(sigma, color, target_color):

# Compute the accumulated density along the ray

alpha = 1 - torch.exp(-sigma * delta_t)

# Compute the predicted color along the ray

pred_color = torch.exp(-alpha * sigma) * color

# Compute the reconstruction loss

loss = torch.mean(torch.sum((pred_color - target_color) ** 2, dim=-1))

return loss

- Sampling Strategy: We sample rays from the input images, and along each ray, we sample points using a coarse-to-fine strategy—more points are sampled near the surfaces.

- The NeRF model is view-dependent, meaning the predicted color (\mathbf{c}) varies with the viewing direction (\mathbf{d}).

- Positional Encoding (e.g., Fourier features) is applied to the 3D location (\mathbf{x}) and the viewing direction (\mathbf{d}) to enable the MLP to represent high-frequency variations:

class PositionalEncoding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, max_freq, num_freq_bands=6):

super(PositionalEncoding, self).__init__()

self.max_freq = max_freq

self.num_freq_bands = num_freq_bands

def forward(self, coords):

# Scale the coordinates to fit within the range (-1, 1)

coords = coords * self.max_freq

coords = coords.unsqueeze(-1) # Add an extra dimension

# Compute sinusoidal positional encoding

freqs = torch.pow(2.0, torch.arange(self.num_freq_bands).float() / self.num_freq_bands)

sin_input = coords * freqs * (3.14159 / self.max_freq)

cos_input = coords * freqs * (2 * 3.14159 / self.max_freq)

pos_encoding = torch.cat([torch.sin(sin_input), torch.cos(cos_input)], dim=-1)

return pos_encoding

References

- [1] State of the Art on Neural Rendering

- [2] Voxnet: A 3D convolutional neural network for real-time object recognition

- [3] A point set generation network for 3D object reconstruction from a single image

- [4] AtlasNet: A Papier-Mâché Approach to Learning 3D Surface Generation

- [5] Occupancy Networks: Learning 3D Reconstruction in Function Space

- [6] Marching Cubes: A High Resolution 3D Surface Construction Algorithm